I recommend: Eleanor Clark

Being married to one of the most decorated linguists of the 20th century may be why this woman is being forgotten.

This is the fourth issue of WRITTEN OUT, a twice-weekly newsletter about women’s literature (past and present). You can read the intro issue here.

You’ll love Eleanor Clark if you love: Annie Dillard, T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland”, reading Travel & Leisure, or Madam Bovary.

Eleanor Clark found me. Her book arrived in the package room of my apartment building in January. It was wrapped carefully, as many of the books I order are, in a combination of bubble-wrap, a makeshift cardboard robe, more bubble-wrap, all tucked tightly inside a shipping box. The book, Oysters of Locmariaquer, was old but not that old. It was published in 1964 the same year as Herzog by Saul Bellow and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl. I definitely purchased it. I bought it for whatever reason on December 11, 2016.

I have no memory of what brought this book to me. Perhaps it was one of the dozen rabbit holes I fall into online every day. Perhaps someone recommended it to me and I promptly forgot. Either way, I didn’t get around to reading it until mid-February and promptly fell in love.

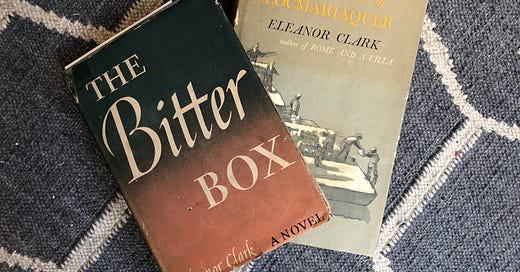

Sometimes, when I’m around my husband’s brothers the cadence of their words match his. Vocal rhythms are a strange, learned, familial tick. I only notice it in them because I have loved their brother for a long time. I am surprised to hear it coming from someone who is not him, but that mirrored lilt feels comforting and affectionate. Reading Eleanor Clark’s Oysters of Locmariaquer (and later her first novel The Bitter Box(1946)) felt like that: like a vocal rhythm so loved it is shocking to find it outside myself.

Let me show you. Oysters of Locmariaquer is, on its surface, a book about oyster breeding. But it is only about oyster breeding the way Easter is about bunnies. Here’s a passage I love

“Coste and a few other scientists were getting warm, as you might say, about the sex life of the oyster. Science was young and passionate in those days, so short a time ago; the great truths, the Truth itself, flickered grail-like behind every leaf and shell and over the grind of the lab, where the coming race of mere technicians hadn’t yet cast its pall. This is where our time goes most crazy; it’s an old inner tube with a couple of dogs quarreling over it; if it’s a yardstick it will wrap itself around the world and be insufficient to measure the common caterpillar. Geological time, with margins of error of mere millions of years, is more comfortable to move in than the last hundred and twenty-odd, if you start imagining one by one all the hunches, experiments, discouragements, hours of ghastly boredom and everything else on the part of a number of people, that went into finding out anything about anything, such as the births of mountains or how the oyster procreates.”

This paragraph is obscene in the risks it takes, the journey it begs its reader to follow. It created in me a love that feels like a wave of nausea, building slowly, moment by moment until the quaking feeling demanded attention. This book won the 1964 National Book Awards for Arts & Letters (now non-fiction).

It is a book of travel fiction, I guess. It is a book that transports you fully inside the oyster and inside the small town working until with hands are chalked with salt and joints inflamed with arthritis that keeps the oysters breeding. “We ‘scavengers’ are not purveyors of facts. We are keepers of echoes and conservationists of memory,” Clark said in 1965 at a conference put on by the Arizona Republic. “Nature is vanishing and with it man’s sense of history. The oysters of Locmariaquer stirred up the conscience of those things in me.” What a way to think of the work we do as writers: as scavengers, as keepers of echoes.

Clark’s earlier book Rome and a Villa is still considered one of the best American travel books of the 20th century. I haven’t gotten to it yet, because I am trying to savor my time with Clark, and she was not prolific enough for me to speed through. You only get to read something for the first time once.

How had I never heard of her? I posted a photo of the book on Twitter and found a couple of fellow fans but not many. In one generation, she’s been disappearing.

The only reference to her in the Paris Review is in an excerpt from John Cheever’s journals in which he writes.

“Her scholarship is exacting, her knowledge of the city lyrical and intimate and grown, hard-headed men on finishing the book have been known to take the next plane to Fiumicino. These qualities of scholarship, lyricism and humor and deep intelligence characterize all of Eleanor’s work.”

The next sentence?

“Eleanor is an exceptionally beautiful woman —a graceful athlete, a formidable linguist and a pleasant mother.”

While I am sure those things are true, it is easy to lose in that complementary sentence the phrase “formidable linguist.” Her wikipedia page is seven sentences long; two of those sentences are about her marriage. Clark was surrounded, her entire life, by writers who were more popular than her, and it may have dwarfed her immense talent in our rearview mirror. At Vassar in the 1930s she was friends with Mary McCarthy and Elizabeth Bishop. Her husband was such a shining sun in literature it is almost incredible she got noticed at all. Eleanor Clark was married to Robert Penn Warren.

Penn Warren was one of the most decorated poets in American history. He won the Pulitzer prize for poetry in both 1958 and 1979 AFTER winning the Pulitzer for fiction in 1947. He was a U.S. Poet Laureate. He founded The Southern Review. Both he and Clark were Guggenheim fellows. In almost all of my research of old newspaper interviews with Eleanor Clark, she is interviewed with Penn Warren.

It’s understandable. Theirs was a literary marriage built for envy. She claimed their whole marriage that she was the one who had pursued him. Together they had two children. They lived in an old house in Connecticut on some land. In the mornings, they parted to work on their writings in their separate studies on opposite sides of a renovated barn. She wrote at the typewriter with their cat on her lap. He wrote in longhand with their dog under his desk. At 2:30, they met for lunch for an hour before returning to work. In the evenings, they read. When Clark was 64 years old, her eyesight began to fail and Penn Warren read aloud to her in the evenings for the last decade of their marriage.

Penn Warren died in 1989. Eleanor Clark died in 1996. She was not as decorated as him clearly, and her work was more languorous, more ruminative, more deeply female. There is something soft about the shape of her sentences that makes them flow easily forward. Her momentum is gentle. It is easy to wonder if perhaps she had been married to someone less successful, she would have had more of an opportunity to shine.

On Tuesday we will have our FIRST INTERVIEW with a debut novelist!! Paid subscriber only issues will begin on Friday, March 22!

If you have tips, links, gossip, someone to interview, a book to promote, or just thoughts and feelings, email me at mckinney.kelsey (at) gmail.com.