Imagine getting dragged in your own obituary

The life, death, and burying of one of America's first famous female novelists.

This is the second issue of WRITTEN OUT, a twice-weekly newsletter about women’s literature (past and present). Thank you so much for subscribing! I’m so excited about this issue, and hope you will be too.

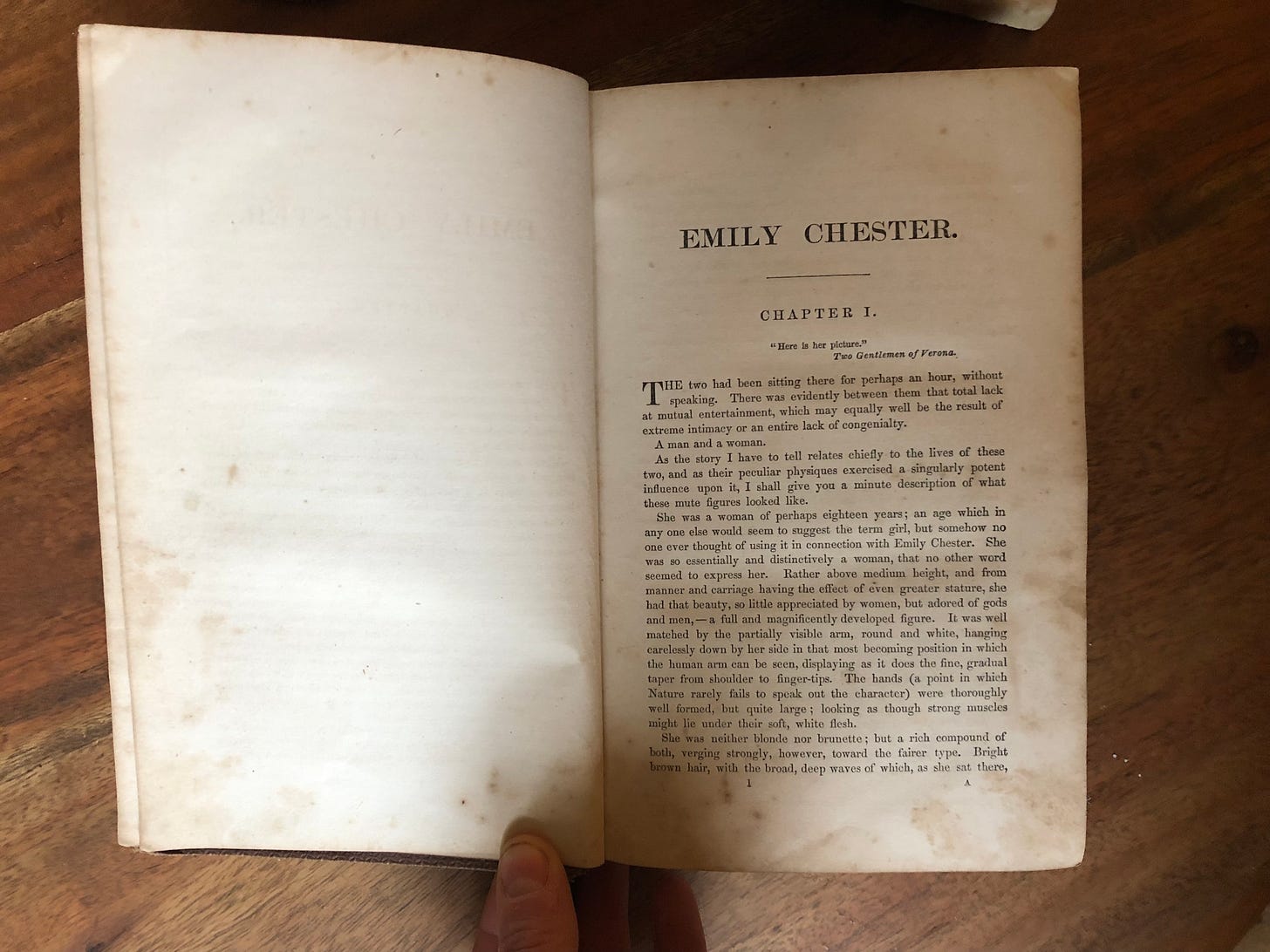

Nothing screams scandal like a novel without an author. When Emily Chester was published anonymously in 1864 in the midst of the Civil War, it became an automatic sensation. The book was too uncouth to put its female author’s name on the cover. Quickly, though, it sold through 10 editions and was published in Europe. It even was transformed into a fairly well reviewed traveling play (the 1864 equivalent of an HBO adaption).

Eventually its author was revealed to be a Baltimore woman, 26 years old at the time, named Anne Moncure Crane. It was her first novel.

The plot of Emily Chester is now familiar. There once was a man who Emily was drawn to, but he wasn’t in love with her. So our heroine, because of her Puritan background and her grief after her father’s death, makes a bad decision and marries a man that she finds sexually repulsive. “There is,” our narrator says in reference to this union, “a certain degree of heart starvation which will kill any naturally constituted woman.” Her marriage is compared to “the old torture, binding a dead body to a living one.”

There’s no real twist coming. Emily is stuck in her marriage, and simply suffers for the rest of the novel. This is 1864, after all. She dies of a broken heart, lying up to her last moment that she had been happy. Here was the scandal: this wasn’t a minor character stuck in a loveless marriage; it was the heroine. Here was an American Madame Bovary, written by a woman, thirty five years before Kate Chopin’s The Awakening.

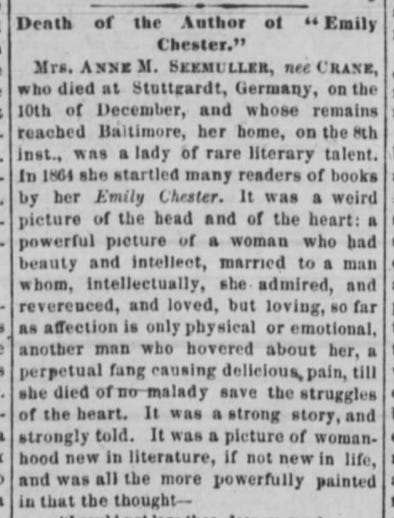

Crane ignited a shift in women’s literature: the unhappy marriage, the unhappy wife, the unhappy ending. A cohort of women including Louisa May Alcott, Harding Davis, Adeline Whitney, and Elizabeth Stoddard pushed fiction by women into a new maturity in the five years after Emily Chester’s release. Their heroines were beginning to become sensual, to yearn for more than they were given. Emily Chester was critically adored and massively popular. Crane went on to publish two more novels, and a post-humous book of essays. She died in December 1872 at 34 years old. Her novels were still selling well, and still critically beloved.

Let’s have some proof. An obituary written in the Cincinnati Enquirer on January 20, 1873, reads

“None of our literary women have revealed more insight into, and more ability to analyze character than Miss Crane [...] few American novels will hold a place in literature higher or hold it longer than the strange, subtle, metaphysical, graceful Emily Chester.”

Except, of course, we know that it didn’t. Emily Chester’s reputation would barely live another year after its author. Today, Anne Moncure Crane’s name is almost never uttered by anyone.

And now it is time to reach our scandal, our gossip, our second piece with no byline.

On January 30, 1873 an obituary for Anne Moncure Crane ran in The Nation. It did not have a byline and is deeply ill-natured. It begins by saying

“[Emily Chester] will not now be recollected very well by many people, as its success was in reality essentially an ephemeral success, and the reputation it procured for its author fleeting.”

Remember: this is an obituary. The piece goes on to call the novel crude and a basic version of Goethe, before accusing Crane of having written it in a silly little women’s club. The piece concludes with this line:

“The somewhat unfortunate plot of “Emily Chester” was a matter of no significance.”

It is a brutal pan, an effective killing of a novel, but it’s also a lie. Emily Chester was significant. It kicked off a movement in women’s writing that men would eventually take as their own (women’s internality and unhappiness in marriage). Only 9 years before, it had been a bestseller. It had been reprinted that year and was still in bookstores.

Why doesn’t this obituary have a byline? What is being hidden from the reader? Why would this, of all things, need anonymity? What did the writer have to fear? There was no SWAT team doxxing happening in 1873.

Sheila Liming, Assistant professor of English at The University of North Dakota, makes an argument in her 2017 essay An Impossible Woman: Henry James and the Mysterious Case of Anne Moncure Crane that this reduction of a woman’s career to nothing more than a school-girl story was written by the later famous novelist Henry James. But at this point he wasn’t famous. In 1873, James was still two years away from his breakout novel.

What’s Liming’s evidence? It’s good. Liming points out that James was a regular contributor to The Nation. In 1873 he was one of the magazine’s chief literary reviewers, and he had an already avowed hatred of Emily Chester. He had panned it in The Nation upon its release and the review bleeds with envy and bitterness. It has the same ring of fury and complaint that appears in the unsigned obituary.

Why would Henry James want to kill the legacy of a very popular American novelist?

What’s the nice way to say this? Let’s have a man do it. Alfred Habegger in his book calls what James did “the slightly risky enterprise of appropriating and rewriting [Crane’s] novels [...] a civilized and responsible act to turn her shapeless and immoral narratives into a novel of rounded perfection.”

Now we are not going to be nice.

What James really did (whether he wrote this obituary or not) was steal pieces of Crane’s work, rewrite it in his own voice, and pass it off as his own. We call this: plagiarism. Particularly interesting are the massive parallels between Crane’s last novel Reginald Archer and James’ The Portrait of a Lady, published after her death. Here’s a very surface-level parallel. The heroine of Crane’s novel is named Christie Archer. James’ heroine? Isabella Archer. This isn’t just plagiarism; it’s LAZY plagiarism. I do not have the energy to get into the plot similarities, but look it up.

This gets worse. The promise that the obituary makes that “[Emily Chester and her author] will not now be recollected very well by many people,” was a threat enacted. After this obituary probably written by Henry James ran, Emily Chester would never be printed again. Today its prediction rings true. No one knows about Emily Chester anymore.

But is that because the book couldn’t stand the test of time? Or because it wasn’t allowed to? In Emily Chester, I found a fascinating heroine, a gorgeously rendered world, and an author whose literary risks still stand out. It does read like a 19th century novel, but plenty of those still find praise.

Right after the title page, in the first edition of the novel, an epigraph reads: “It is in her monstrosities that Nature discloses to us her secret.” The monstrosity of this story, our story, is clearly that Anne Moncure Crane Seemueller and her work has been so fully forgotten. The secret revealed is that she wasn’t forgotten naturally. She was erased.

You can read Emily Chester online for free. Emily Chester is currently not being reprinted by any publisher.

If you like this newsletter, please subscribe! If you love it, please pay me to find more of these stories!

This newsletter is new! Not all of the issues will be like this. Read the introductory issue here. If you have tips, gossip, someone to interview, a book to promote, or just thoughts and feelings, email me at mckinney.kelsey (at) gmail.com